Malta’s national holiday, Victory Day, is probably the hardest-working national day, since it covers four separate events. In a predominantly Catholic country, the 8th is the Nativity of Mary, commemorating the birth of the Virgin Mary. The Great Siege of Malta also concluded on this day in 1565 when the Ottomans finally pulled back, leaving the city to be relieved by Spanish and Italian soldiers. The French gave up their two-year blockade almost exactly 235 years later, which confirmed British rule of the island. Finally, during World War II, the Italian Siege of Malta was called off on October 16th, 1942. (It’s about a month off, but as long as you’re celebrating, might as well round up.)

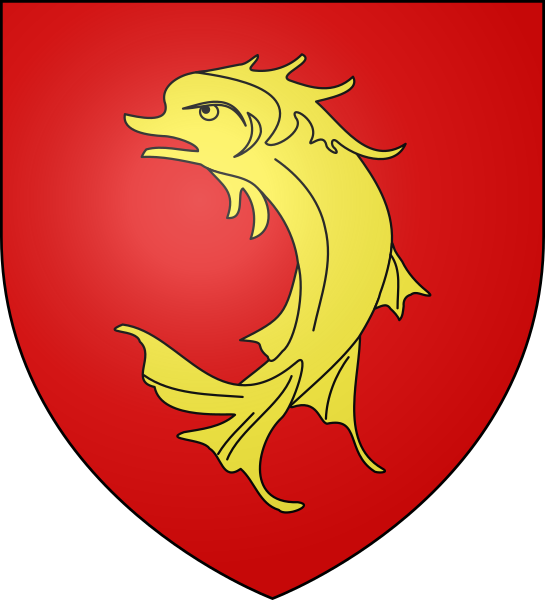

Somewhat counterintuitively, the Maltese arms do not involve a Maltese cross. Instead, they feature the George Cross, the second-highest award in the United Kingdom. The entire island was granted the award for their courage and heroism under the Axis siege. When Malta declared independence in 1964, the collective award went directly on both the flag and their arms.

The Maltese cross makes only one appearance in Malta’s heraldic history; starting in 1875, it used a colonial badge of per pale argent and gules, a Maltese cross argent. The field was almost certainly drawn from the city arms of Mdina. The cross was (correctly, in my opinion) removed in 1898, and in 1943, a chief azure was added with the George Cross proper.

Even with such a relatively short timespan, there is still a somewhat awkward coat of arms jammed in to Malta’s history. In 1975, the new Republic of Malta decided to switch out the previous coat of arms, concerned about its visual recollection of the monarchy. Unfortunately, what they decided to switch it to was… shall we say, not particularly traditional? Designed by a class of art students, the new national emblem limped along, attracting criticism from heraldic experts, until it was mercifully replaced in 1988, with some modifications to the crest, supporters, and motto. (I should say that I don’t remotely blame the art students; they evidently thought they were designing a new passport cover, and I think what they produced would suit that purpose quite well! It’s just not really a coat of arms.)