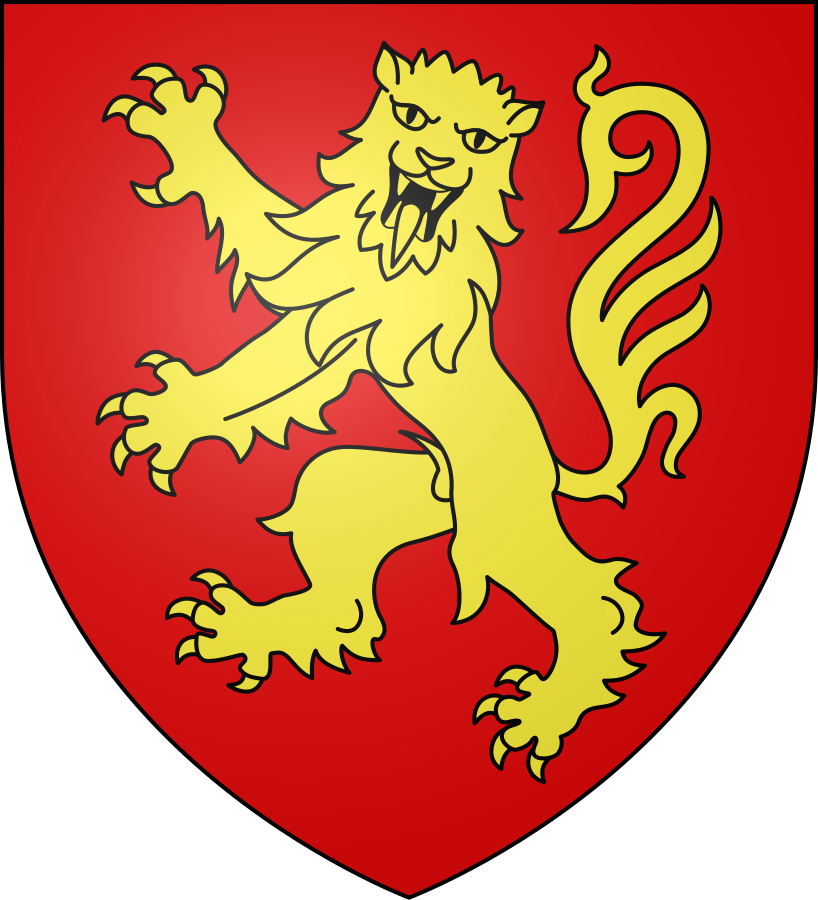

(c. 1220? – 1291)

From the Dering Roll (c. 1270-1300)

Blazon: Argent a sword palewise point in chief sable

Several other blazons for the Marmion family conflict with this depiction, showing vair a fess gules (sometimes fretty or otherwise ornamented or). It’s possible these are family arms – it would be odd for a baron not to have his own arms, and it does look like Philip had that title. However, the arms on the Dering Roll are probably the arms of his first wife, Joan, heiress to the Kilpeck family (so Philip would have had the right to bear them, albeit in pretense). The exact tinctures of the Kilpeck arms and the positioning of the sword seem to be flexible, but they’re close enough that I’m fairly confident in this assumption. I did manage to find a lovely photograph of the tombs of Sir Philip and his second wife, Mary, but there’s not enough detail on his shield to confirm which arms he was using at the time of his death.